The Burrowers: Animals Underground Part 1 (Rabbits)

Last night the BBC broadcast the first in a new series: The Burrowers: Animals Underground presented by Chris Packham. It aims to observe what badgers, water voles and rabbits get up to whilst they are underground by building and stocking artificial tunnel systems accessible to cameras. Just in case you missed it, here is a review of the first episode. I’m just going to talk about the rabbits, but the badgers and water voles were certainly interesting too.

Investigating a Real Rabbit Warren

The program begins by exploring an empty rabbit warren at Bicton Park Botanical Gardens, Devon, to create a template to built an artificial warren from. To do this they pump smoke into a tunnel entrance and look for where it escapes to reveal the other entrances and exits (they find 13 in all). Next, in steps Tanya the ferret, fitted with a beacon transmitting position and depth, she reveals the tunnels reach 2.5m underground at their deepest. The tunnel diameter is around 20cm, with multiple chambers about twice the size of a football.

Although not shown in this episode, the trailers for next week (and some online articles) hint at a more extensive exploration of a set by filling it with concrete and excavating the resulting mould.

Creating an Artificial Warren

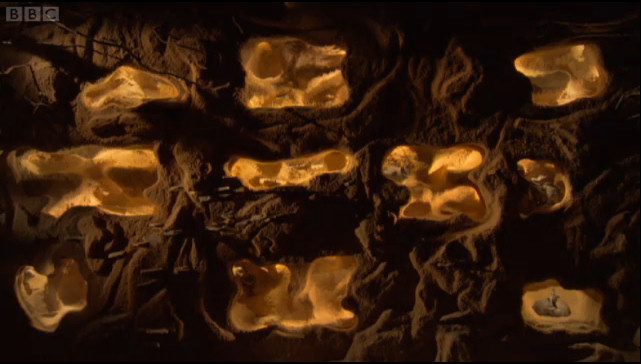

With a real warren for a template, they next set about building an artificial one from concrete and fibre glass, with an adjoining observation room (entered via a hobbit door) allows the cameras to view a cross section through the warren. I noticed the tunnels in the artificial warren were 25cm, rather than 20cm, perhaps to accommodate the slightly bigger bottoms of domestic rabbits (which we learn later will be the occupants rather than wild rabbits).

The cross section through the artificial warren, allowing observation of the rabbit inside through glass.

The warren leads out into a large ‘pen’ which is meshed over the top, providing much better security that the natural warrens top covering of brambles and rendering the rabbits completely safe from predators. They also replace the soil with sand “to reduce the chances of parasites” and there is no sign of grass only some gorse bushes, which by the speed the rabbits were tucking in will not last long! We aren’t shown/told about their feeding regime.

The artificial warren is certainly a brilliant design, I’d love one in my back garden! But, I can’t help but wonder if creating an environment to observe rabbit behaviour in which the rabbits can neither dig (the warren walls are concrete after all) or graze, two of the iconic rabbit behaviours isn’t a little bit limiting.

Sourcing ‘Wild’ Rabbits

When it comes to the inhabitants on the warren, we are told that the wild rabbits were too aggressive, specifically with other rabbits, and they were also “skittish and they were easily frightened”, so they have chosen to use domesticated rabbits with agouti colouring. Dr Sasha Norris, the rabbit advisor, justifies this by saying:

“Rabbits were only domesticated very recently and so inside each household rabbit is a wild rabbit waiting to come out. in fact a whole suit of genetic behaviours are in there and once put into a natural type situation they will express themselves”

I can’t help but thinking either the behaviour is so close they are interchangeable, or the behaviour of wild rabbits is significantly different enough to make them unsuitable – you can’t really have it both ways. I agree that domestic and wild rabbits are very similar in behaviour, but again, one of the dominant factors in rabbit behaviour is they are prey and in the wild this makes them hyper-vigilant and skittish – they need to be to survive. Most of our cottonwool wrapped domestic pets never learn to be scared, even Scamp, who is genetically a wild rabbit hasn’t got the sense to know when to be cautious e.g. he happily hoped up to a cat for a sniff. Whilst that’s a desirable quality in a pet, it’s not very representative of wild rabbits. So we are observing ‘wild’ rabbits that can’t dig, graze and have no fear of/from predators.

The Warren Inhabitants

Ten of the domesticated rabbits (we later learn 8 females and 2 males) are initially introduced mid winter “to reflect the winter population of a small warren in the wild”. As you expect they immediately set about working out the hierarchy. We are told Thumper (orange tag), the dominate male, regularly chases Peter (purple tag), the other male, out of the warren.

The does also fight for dominance, in answer to “how do they display their power” we treated to a shot of a squirt of urine from dominate female Hazel. As Packham points out, a natural warren would be completely dark, so body posturing wouldn’t be visible. Stinky urine on the other hand works a treat and lands Hazel her choice of nesting chamber.

There is no particularly aggressive aggression shown, a little chasing but no actual fighting. It would be interesting to know if this is because there is plenty of space (the warren was built to house a larger population that the initial ten) or the rabbits are already used to each other and we weren’t shown their more serious attempts at working out the boss.

Breeding

They also quickly set about multiplying. We are told that after a quite relaxed period, at a certain point in winter everything changes, with a surge in hormones, with the warmth and security of a warren allowing rabbits to breed as early as January. Now, I don’t know how the rabbits lived before, but I would guess they probably weren’t subjected to the temperate and resource availability (amount of food) that help regulate when rabbits breed. So typically for rabbits, four weeks later the first litter is born (and I don’t imagine the seasons have anything to do with it).

There is footage of Hazel giving birth to five babies and minutes later leaving to go outside an feed, behaviour that is replicated by the other mums. A heat sensitive camera shows that the fur lined nest is incredibly good at insulating them allowing the mum to leave them rather than providing warmth. The kits constantly wiggle and rotate position each getting a turn at being in the middle.

Hazel nursing her babies – the white/light blue areas show heat.

When Hazel visits to nurse the babies, which she does only for a few minutes every twenty-four hours (made possible because rabbit milk is much richer than most mammals), the same camera also shows how well insulated Hazel’s own coat is with heat only escaping from her the ears.Whilst I don’t think there is any behaviour here not already well documented, the footage of the babies in the nest is excellent and certainly has the aww factor.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s definitely an interesting look into rabbit behaviour, but I’m not entirely convinced how accurately it will portray wild rabbit behaviour, we’ll have to see what next week brings!

You can watch it on iplayer here and find out more about the series here.

Did you see it? What did you think?

Tags: Behaviour, wild-rabbit

They REALLY could have used you as a consultant…

I have to agree with you as far as it not being cutting edge research into wild rabbits. They made it seem like the once a day nursing was new info, but I heard that just the other day from a House Rabbit vet lecture…The warren they built is awfully neat. And the Water Vole expert looks just like a Water Vole with his beard and round face.

I think it is the worst wildlife pornography they have managed to think up to-date.

As if just by (finally) admitting the footage is not shot in the wild makes it all ok !

It’s a real shame, and a bit of a cheat, they didn’t film actual wild rabbits. The private life of the rabbit by R.M.Lockley covers studies done in artificial warrens in the 1950’s and has much information on their social behaviours.